Key Points

- Decentralism favors decentralization; having fewer single points of failure in a system, making it difficult to capture.

- In blockchain systems, decentralization is extremely important. To make a blockchain useful, a certain threshold must be met, depending on the application.

- Many projects use the difficulty of measuring decentralization to obfuscate their true susceptibility to capture.

- Social and technological layers can be captured through various means, so they must both be decentralized, and should not rely on a central group.

- Ethereum Classic aims for a Sovereign Grade level of decentralization, meaning that no worldly organization can capture it.

- Ethereum Classic applies a principles first approach, decentralization maximalism, checks and balances and protocol neutrality to achieve long term capture prevention.

Introduction

One of the first publications about Ethereum Classic that came out after The DAO Hard fork was A Crypto-Decentralist Manifesto. In protest of The Fork, it underlined the classic decentralized approach to organizing blockchain projects. This document set the tone for ETC's future development. Since its creation, much has been discovered about the nature of the elusive but vital concept.

Decentralized, Immutable, Unstoppable.

- Ethereum Classic Website, 2016

This series of buzzwords is a recipe for unlocking the true value potential of blockchain technology. First you need decentralization, which enables immutability, allowing unstoppability, and making possible the bright future we discussed earlier.

Quantifying Decentralization

Decentralization is the process by which the activities of an organization, particularly those regarding planning and decision-making, are distributed or delegated away from a central, authoritative location or group.

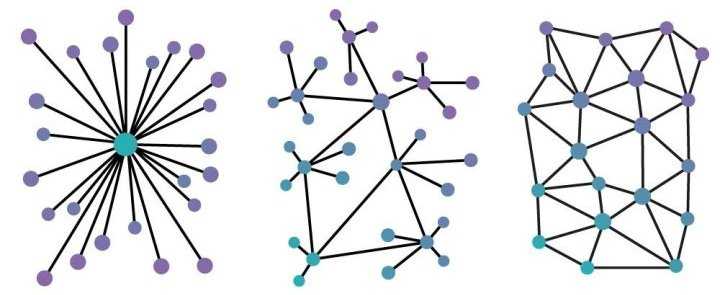

Decentralism favors decentralization, a property that exists in many systems and forms throughout nature. It is not a binary property, but a spectrum that ebbs and flows through time. It's difficult to articulate a hard and fast definition for decentralization in all contexts, but it can be visually understood fairly intuitively.

In the realm of blockchain projects, there are many ways of measuring decentralization, with one rough quantification being "the ratio of people needed to be compromised in order to take over the system". That is to say, if an attacker wanted to control or censor a chain, a project that required them to compromise 80% of participants is more decentralized than a project that only required 10% to be compromised.

This measurement is known as the Nakamoto coefficient, and while it is an excellent conceptual tool, is a fairly low-resolution one-dimensional measurement. In reality, decentralized systems can be designed to make capture less likely by assigning different groups with different responsibilities. Due to their diversity of responsibilities and backgrounds, difficulty in capturing a network then becomes linked not simply to the ratio of people, but a complicated mesh of overlapping strengths and weaknesses of different actors within the system.

For example, in Proof of Work blockchains, an accurate measurement of decentralization would attempt to take into account mining by reward, clients by codebase, developers by commits, exchanges by volume, nodes by count, and ownership by value distribution, etc. But even this more nuanced approach is far from perfect, as a single snapshot measurement does not yield much insight into whether a system can maintain decentralization over time.

Whichever way it is quantified, attackers that wish to "own" the system have a more difficult job the more decentralized a project is. To defend against take-overs, projects need to reach a sufficient level of decentralization, which means minimizing the number of central points of failure and bottlenecks, which can exist in many places in the system.

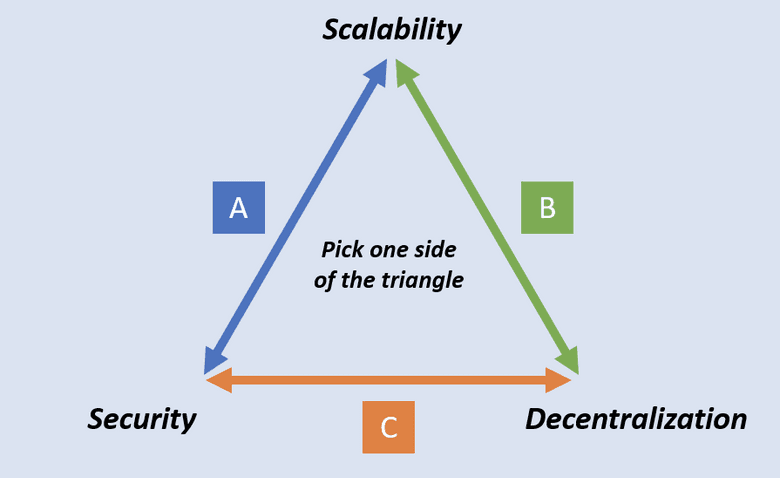

The Blockchain Trilemma

The underlying structure of decentralized networks comes with unique challenges as compared to centralized networks. As early as the 1980s, computer scientists developed what’s called the CAP theorem to articulate perhaps the most major of these challenges. According to the CAP theorem, decentralized data stores — of which blockchain is an iteration — can only provide two of three guarantees simultaneously: consistency, availability, and partition tolerance (CAP). In the context of modern distributed networks, this theorem has evolved into the blockchain trilemma. This is the popular belief that public blockchains must sacrifice either security, decentralization, or scalability in their infrastructure.

- The Blockchain Trilemma, Gemini.com

The Blockchain Trilemma describes a technological limitation that applies to all blockchain protocols. A similar concept also applies to the social layer of a blockchain project, with a sliding scale of top down vs bottom up decision-making.

Like creating a video game character, all projects must place themselves somewhere in the space of these sociotechnological dimensions, allocating ability points and sacrificing some attributes for others. The selection defines a blockchain's class, abilities and effectiveness in battle.

As we will see, as far as the protocol's attributes and underlying philosophy goes, Ethereum Classic has maxed-out it's decentralization and security, intentionality sacrificing both transaction scalability and top down social organization so that more essential skills can be strengthened.

ETC chose to max-out these skills because for a blockchain protocol to scale its base protocol it must make trade-offs in decentralization and security, which may not appear as apparent costs immediately, but in the long run is bound to damage the utility and value of the network. In short, for ETC, scalability is less important than security and decentralization, and this technical trade-off is also mirrored in the social layer; decentralization trumps the expediency of central rule.

Today, most blockchain projects have abandoned the idea of maxing-out decentralization in exchange for scalability and the benefits of coordinating from a central group. This may well be useful for short term bootstrapping as it allows the funding of extravagant development or marketing budgets, and there is no obvious downside in an environment that is not antagonistic, but unless the project tapers-off this dependence on centralization, which may be impossible due to the incentivization structures it creates, the network is exposed to take-over through the capture of this relatively centralized set up.

Sovereign Grade Censorship Resistance

One question that should be asked when evaluating different blockchain projects is "is it decentralized enough?". The answer to this entirely depends on the use case's threat model, which depends on what kind of applications need to be run on a given chain. The question can be reframed as "who would want to stop the applications on this chain from running, and can the chain resist their attempts at censorship?".

For example, in the case of Bitcoin, its main application is the coin itself: digital scarcity and the ability to transfer it without censorship. It competes with many currencies and assets, including the US dollar, and therefore it must withstand attacks from very powerful entities to persist. Many of Bitcoin's predecessors were shut down because they had central points of failure, and Bitcoin was explicitly designed to circumvent this kind of censorship by being sufficiently decentralized.

In contrast, some blockchains require less censorship resistance than Bitcoin and only intend to, for example, enable the transfer of virtual baseball cards, or have other uncontroversial use cases. As no powerful external forces want to stop these applications, censorship resistance is unnecessary. It may even be seen as a benefit if some central party can override the state of the chain in certain circumstances, so having the whole chain operated by a handful of authorities is acceptable for this use case. In these cases, where the use case is not important enough for a well-funded organization to shut down, it might make sense to sacrifice decentralization for scalability, and other non-blockchain technologies may be more appropriate.

Ethereum Classic, even back in 2015 when it was known as Ethereum, set out to achieve ambitions on a level at least as prone to censorship as Bitcoin.

Ethereum is a decentralized computing platform that executes smart contracts. Applications are ran exactly as programmed without the possibility of censorship, downtime, or third-party interference.

- Ethereum.org, 2015

Ethereum's Smart Contract Platform was designed to not only support Bitcoin's base currency use case, but also any kind of blockchain application. Because of this, it is highly likely to attract attempts at censorship from legacy system incumbents at risk being disrupted.

To provide a solution on a global level that would need to stave off attacks from other sovereign institutions such as nation states and multinational organizations, Ethereum, like Bitcoin, would need to reach a level of decentralization that made it impossible for any of these groups censor it; Sovereign Grade Censorship Resistance is required.

A critical threshold is reached with this level of uncensorability. As no other institution can censor the network, applications become significantly more useful, becoming trustless. They no longer rely on the trust or permission of some other company or government to operate, and, on these platforms, it is the users, rather than the providers who get to decide what goes on.

Code is Law can only operate on chains that have achieved Sovereign Grade Censorship Resistance. This level is required to prevent other entities from censoring its operation, and this in turn requires the chain to max-out it's decentralization attributes and constantly maintain them without compromise. Code is Law requires decentralization maximalism.

Centralization Failure States

Before we explore the solution to the problem of centralization, we must first understand how a lack of decentralization can quickly regress into full-blown failure.

Today, even more so than when Ethereum (Classic) was launched in 2015, it is increasingly apparent that censorship is becoming the weapon of choice of a dying legacy system attempting to cling on to relevance. As these old institutions become increasingly threatened by change, it seems likely that ever-more drastic measures will be taken to defend their position.

Before the internet and blockchain technology entered the scene, these institutions had reality pretty much on lockdown as society was heavily reliant on centralized control points for value and information transfer, which was readily exploited. With cryptography, Satoshi retorted just in the Nick of time, turning the tables on the logic of violence, and providing humanity with a path towards an alternative emergent order.

As time goes on, the attacks against free, fair and open alternatives to the status quo will ramp up. As a result, the cryptocurrency ecosystem will enter a new phase, a highly antagonistic phase, where the uncensorability of blockchain technology will truly be put to the test, and the central points of failure in cryptocurrency systems that have them will be sought out and exploited. For use cases that incumbents disapprove, only the Sovereign Grade will survive.

In the future, to maintain utility and value, blockchains must resist a range of social, economic and technological attacks that will be deployed against them. The list of attacks is ever-growing and new forms of attack are sure to be conjured up and countered, but for now, at the very least, the more obvious known failure states must be avoided.

The Ephemeral Foundation

Historically, the number one cause of death for blockchain projects is when the teams responsible for maintaining them no longer operate. Simply put, if a project depends on a central organizing committee or developer team, it will only last for as long as that organization does.

Organizations can cease to operate for many reasons. Be it a simple rugpull, running out of funds, getting hacked, getting hammered by regulators, traffic accidents, or any other reason, these factors are often outside the control of this team, so it is down to luck or the approval of regulators whether a project can survive.

In many cases, the existence of a central team disincentives others from contributing to a project, as they are not on a level playing field. Third parties will always be second class citizens compared to this central organizing committee, who are calling the shots and disproportionately benefitting from price action in the case of a premine or development tax, which further solidifies reliance on this team to maintain and direct the project, and, at the very least, prevents a natural organizational hierarchy from emerging.

This reliance on a central team may provide direction and big budgets in the short term, but it burdens the protocol with a kind of "centralization debt" that is difficult to pay off. Eventually, like all organizations, the central team will cease to operate. Unless the project sheds this reliance, it is likely to become either abandoned or maladapted to life without this group.

Meatspace Capture

For high value projects that have an overreliance on centralized teams, as time goes on, a fate far more insidious than mere abandonment becomes increasingly likely. Like clockwork, as with all top-down centralized institutions, they become captured by special interests through various manipulative techniques.

Suppose a powerful institution feels threatened by new technology. Rather than stamping it out, which may be impossible, it is far more effective to simply compromise and disrupt its operation by influencing the direction of development in a way that does not fundamentally upset the status quo.

This can be achieved by turning influencers and the leadership of an organization into puppets, whose strings are pulled through a variety of carrots and sticks. Humans are fallible and are susceptible to all degrees of manipulation and extortion; peer pressure, angry mobs, politics, kickbacks, bribes, psyops, honey traps, kompromat, physical threats, imprisonment, or worse.

With enough key targets under the thumb of an attacker, they can control the future of a chain through their authority, making subtle incremental changes that further increase their grip and control over decision-making.

One of the most problematic elements of this type of failure state is that it can be done in a way that is undetectable. It may be that the level to which a central team is compromised is unknown, and capture only becomes obvious when it is too late to do anything about it.

Even if a centralized team is not overtly compromised, the very potential of this compromise can sow distrust and uneasiness. Conspiracy theories and the questioning of decision-making may undermine a project's leadership and stability if they appear not to be driven by merit alone, and simple divide and conquer tactics deployed against the organizing committee may be enough to paralyze the project.

This failure state shows an inherent contradiction within any blockchain project that relies on a central organizing committee. While the protocol may be decentralized on paper, in reality the project is beholden to a central group which can and will be bent to the will of anyone who feels that the cost of doing so is worth it.

Kabuki Coins

Centralization, like gravity, is constantly pulling and looking for any weakness in a sociotechnological structure to find its breaking point. For a system to overcome this force long term, it must ensure that no central point of failure can be exploited, which means designing robust countermeasures that constantly push back against centralization not just in one place but in all areas.

Because of this, there is no point in having decentralization in half measures. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and a blockchain is only as decentralized as its most centralized bottleneck. For this reason, all parts of a blockchain project, both technically and socially, must strive for decentralization maximalism.

Unfortunately, within the cryptocurrency ecosystem the importance of decentralization maximalism is not widely understood or adopted, to the point where the term decentralization theater has become a common way to describe many so-called decentralized systems.

These projects have subtle single points of failure within their systems, but promoters shift the focus to other "decentralized" areas. This is an effective tactic, as proving that a system has potentially capturable central points of failure requires intimate knowledge of the system, and can be very difficult or impossible for the layman, due to the technical skill and insider knowledge required to evaluate properly.

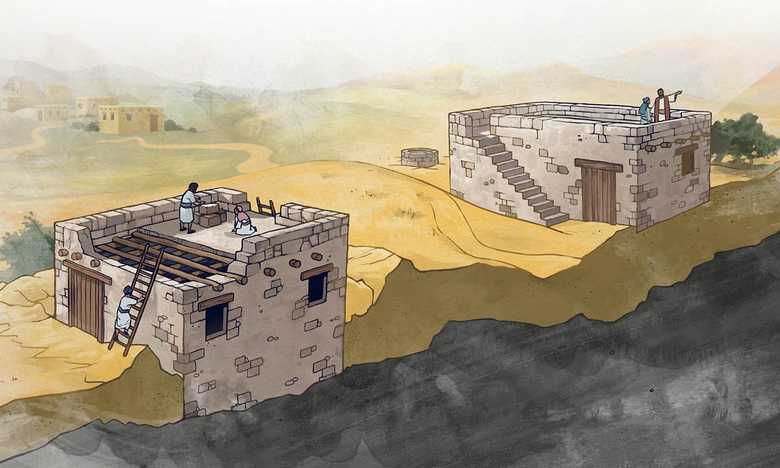

Like the parable of the buildings built on rock and sand, to the untrained eye, two projects may appear to be properly constructed, and under normal conditions they both operate as intended. But under the surface, one project has a fatal flaw that will only lead to ruin in times of stress and will likely end up causing damage to those who expect the project to stand the test of time.

Classic Problems Require Classic Solutions

Corruption is a problem as old as civilization. While it might not have reared its ugly head in the cryptocurrency space yet, as the technology becomes more influential, it is bound to attract forces that wish to bridle its power and shape it towards a future where, far from liberating humanity, blockchains become tools for optimizing enslavement.

In the long run, whatever happens, decentralized blockchains will prevail eventually. Still, if humanity wishes to avoid a dark-ages style period of hampered innovation and stagnation, the word must be spread about the dangers of centralization so that it can be dealt with before they take hold. Luckily, a window of opportunity exists to counter the inevitable ongoing attempts to capture blockchains. For now, projects that strive for decentralization maximalism still exist and are available to those who wish to use them.

While it's still voluntary, rather than relying on authority figures or marketing campaigns, individuals can reason from first principles and reflect on lessons from the past to reach their own conclusions about which blockchains are likely to provide long term value and are worth interacting with.

By going back to the roots of blockchain technology, economic theory and the lessons of history, the wisdom in the design decisions behind Bitcoin becomes clear, and this logic can be reapplied to other technological advancements in the space, including Smart Contract Platforms such as Ethereum Classic.

Principles First

While institutions and the humans that make them are fallible, fickle and fragile, ideas are bulletproof. It is self-evident that technology as important and influential as blockchain must be built upon something more than just people. A well-developed philosophy must act as a strong foundation to guide the actions of otherwise capturable bags of meat.

Good ideas stand on their own, can be debated in public, and are valid regardless of who proclaims them, making them perfect for constructing a harness to restrain and protect the future of a blockchain project. That is why The Ethereum Classic Foundation is not a group, but its principles, which come first and inform decision-making.

Pragmatism is downstream of maintaining and adhering to sound principles, as they enable both practical survivability, long term sustainability, and act as a form of advertising that attracts quality contributors. The principles first approach goes a long way to ensuring that a project can maintain its course for many generations to come, as it is guided not by the ever-changing interests of a central group, but by external philosophical reference points that, even with high a turnover of contributors, can be perpetuated and refined in public to direct the future of the project.

Having no central group to call the shots means that any individual or group can fill any role, as long as they are faithfully interpreting and executing ETC's principles and values, as understood by stakeholders. If some feel that a hard fork diverges from the values they signed up for, they can continue the existing version of the chain. The risk of a chain split means all participants are incentivized to work together to solve differences, and neither side of a debate can overrule the other if the disagreement is unresolvable.

Protocol Neutrality

As the night is young in the blockchain game, the problem of Ephemeral Foundations may not be so obvious. Whether conned, crushed, or otherwise captured, the noble intentions that run the show for many blockchain projects are certain to come to an end, and with them, if their chains are not able to shed reliance, so do their ambitions.

This problem is made worse when the decision-making systems within a blockchain project rely on a central group for extended periods. Alternative mechanisms for organizing the project are unable to evolve, as decision-making is expected to come from the top down rather than bottom up. As a result, opaque autocracy becomes the standard, which ossifies and becomes fragile, rather than allowing for an anti-fragile open meritocracy to flourish.

This manifests in a centralization gravity well, where reliance on central decision-making snowballs as outside contribution becomes more difficult, so the project relies more and more heavily on top-down leadership, and the cycle repeats.

Because of this, in the future, projects that rely on centralized organizations will one by one fall victim to this reliance, and the truth will be realized that only projects without this reliance can sustain themselves for long periods. As the wild valuations that cryptocurrencies currently enjoy depends on the hope that these projects have some degree of longevity, it will become increasingly evident that only truly decentralized projects are worth contributing money, talent or time to, and the market will reallocate accordingly.

Only the projects with long term value propositions will remain, which means only those that don't rely on central organizing committees will remain. By the same logic, it will become apparent that, all things being equal, the projects perceived to be the least dependent on central groups will attract the most contribution and value.

Instead of relying on unsustainable cash injections from central authorities, projects must evolve to sustain themselves purely on natural contributions, such as those through the Buy and Contribute strategy, whereby individuals buy into a project and economically incentivize themselves to contribute to it.

This strategy works best when an individual is reaping the full reward of their contribution, which can only happen when a protocol is neutral. Neutral protocols treat all participants on the same equal footing and do not grant any special privileges to specific parties. Decentralized blockchain projects will compete with each other on this basis; only the most neutral projects, those without a Foundation, Dev Tax, or undiluted premine, will attract the type of natural contribution that enables long term sustainability.

Balancing Power

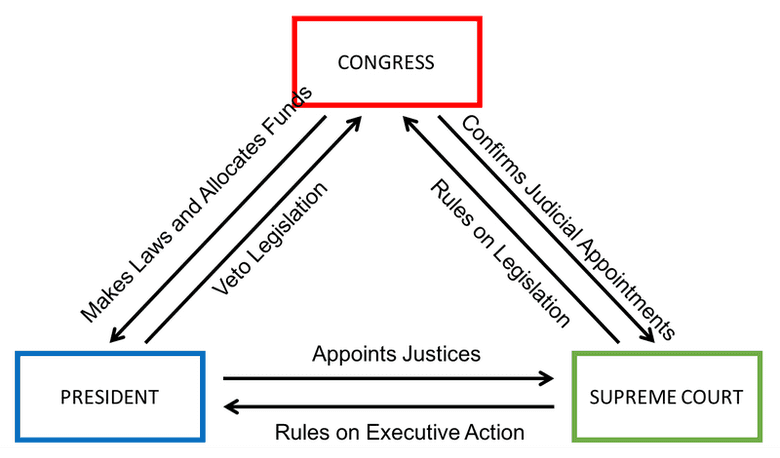

As echoed by the structure of existing institutions such as the government of the United States of America, to rein in bad decision-making and prevent one group from hijacking a system as a whole for selfish interests, a balance of power between different players needs to exist in systems that wish to maintain longevity. This concept is known as checks and balances.

As with the US Government, checks and balances are an essential feature of Proof of Work blockchains, where three major power groups exist and balance each other's power.

| Group | Role | Veto |

|---|---|---|

| Developers | Maintain clients and infrastructure | Stop maintaining code |

| Miners | Provide security against 51% attacks | Mine a different chain |

| Financiers | Provide liquidity and finance initiatives | Sell holdings |

The alignment of three major powers in Proof of Work blockchains provides stability. They each add value to the system in entirely different ways. Each holds the system to account through the power of veto, which ensures that no other groups can screw things up too badly. Whether a government or a blockchain, things tend to go wrong when these checks and balances are interfered with.

Note that this configuration of three is important, as it also means that the collective can overcome consensus issues through a simple majority rule. This odd-number electorate is a common pattern in distributed systems. A deadlock can ensue with only two participants, as no third party is there to resolve the dispute.

The result is a symphony of balanced power, held together by competing interests that incentivize either voluntary engagement or ostracism of bad behavior. Miners provide security and get a block reward, which only has value if the network is useful thanks to developers and other providers maintaining the protocol and building out infrastructure, facilitated by traders providing liquidity and investors speculating and funding projects.

Like struts holding up the base of a tower, these well-placed incentives rely on each other for support. Together, as long as they are correctly distributed, they can yield a new structure greater than the sum of their parts, and can stand potentially for millennia.

On top of this, a diversity of roles makes a system more challenging to take down by encouraging participation from parties with differing interests, profiles, and weaknesses. As multiple layers of defense, the more diverse the pool of participants securing the chain, the harder it is for an attacker to compromise, as a diversity of weaknesses requires a diversity of attacks, and a higher cost is needed to capture the system. Even with the same number of participants, a system with more separation of concerns can be considered more decentralized and difficult to capture because of this diversity.

The blueprint introduced by Bitcoin was also used by many other cryptocurrencies including Ethereum, which essentially copied the fundamentals, tweaked some variables, and (brilliantly) added a Turing-complete virtual machine, the EVM. Much like an architectural blueprint, encoding the structure of a real world building, it would be seemingly unwise to remove one or more of the crucial struts preventing the structure from collapsing into a centralized mess.

If a project wants to survive long term, it must have enough of these necessary incentive structure struts to be properly balanced. If Bitcoin is a sturdy tripod made of miners, developers and traders, by sawing off one of these legs, for example, by switching to Proof of Stake and firing the miners, the result is a two-legged barstool; one that can be straddled for a while, but even the faintest breeze will cause it to become a dangerous liability.

Decentralization Maximalism

Decentralization maximalism is the only known mechanism to shore off the forces of centralization long term. It is not a predefined set of rules but a general philosophy or way of thinking that seeks to reduce the number of central points of failure throughout a system.

It demands that decentralization be pursued holistically in all areas, in protocol's design, and the social layer, where possible. The goal is to make the protocol secure from take-over and the social layer secure from capture. Satoshi Nakamoto being anonymous and going silent is the classic example of this philosophy being applied to the Bitcoin project, the success of which is wise to emulate.

Where it makes sense, by definition, this approach demands no compromise. Even the smallest of sacrifices, infractions, or exceptions should be, unless entirely unavoidable with some overall worthwhile trade-off in the context of known stopping criteria, intolerable. As centralization is difficult to get rid of, it typically accumulates over time and will pile up until the system becomes captured in one way or another.

Whatever the crossroad, decentralization maximalism requires eternal vigilance and the knowledge that systems naturally tend towards centralization, so every decision made must consider the cost paid in centralization debt, to keep the system debt-free long term.

Onward

If humanity wishes to avoid another dark age, it must embrace systems that can resist the corrupt forces threatening to capture blockchain technology's future. Only systems that strive for decentralization maximalism can achieve this, but of all blockchain projects that exist today, only a handful recognize this requirement.

The innovations that Ethereum brought to the world in the form of a Turing Complete Smart Contract Platform provide a great leap forward in terms of the utility and potential of blockchain uses cases, but as evidenced The DAO Fork and the switch to Proof of Stake, the direction the project is being taken makes it susceptible to capture and unable to achieve Sovereign Grade Censorship Resistance.

In the not too distant future, as attacks against blockchains ramp up, this need will be all too clear. As one by one, so-called decentralized projects reveal their true colors and succumb to corruption in the form of capture by special interests. As a result, only the genuinely decentralized will remain.

By combining the technology of Ethereum with the philosophy of Bitcoin, Ethereum Classic provides a secure, multipurpose, decentralized blockchain, and a free, fair and flourishing alternative to what might be a grim and centralized future.